Got (the politics of) Milk?

[PLEASE NOTE, this is an (informal) annotated bibliography, not an essay nor an article. The aim of these is to inspire conversation on topics that are approached anew, or perhaps to aid someone in their practice or research with some cool sources. Most importantly, it is for me to put all my research on whatever topic I am hyper-focussing on during that period into a digital, available and accessible platform for everyone to enjoy as well.]

I picked up this book a couple years ago that stayed with me. It is called The Microbiopolitics of Milk, published in 2022 by Sternberg Press. The book presents the grounding basis for a research project around Milk, done at the INLAND Academy, through its implications in the regimes of contemporary biopolitics, economics and representation. It inspired me to further research the abstraction of Milk, and I thought this might form the basis of this annotated bibliography. I realised after reading it that the book already captures many of the questions I hoped to ask.

So I gave up the topic for a while. I drafted this post and focused on other personal and academic research that had the foreground. This was until last week, when I went to a screening at the Filmhouse in Edinburgh, where I watched Safe, a 1995 film by Todd Haynes. The film follows Carol, a woman in Los Angeles who becomes mysteriously ill. Her symptoms suggest a body that absorbs too much from its environment. Throughout the film, she drinks glass after glass of cold milk (my friend pointed out how odd it is to see an adult drink cold milk with that frequency). Later, an allergist tells her that her body now rejects milk. That moment caught me. It asked what milk means when it moves from a comfort to a threat. It posed milk, this sterile, white liquid, as something that enters one’s identity.

A set of new questions started to form for me, and motivated me to recalibrate the research for this post. The main focus being on how milk circulates across different systems of meaning. Looking beyond how milk is produced and consumed, I started wondering how milk shapes a story or even a body. What languages, laws, and histories gather around this substance? How does milk move through visual culture and the domestic space? The bibliography I have created now follows milk through film, literature, ethnography, and agro-industry, treating it as a lens through which broader political and cultural structures become visible. Further questions emerged along the way. Is milk still a universal symbol of nourishment? What forms of power sustain its status? And what happens when a body refuses it? How do we recognise milk as a cultural force, rather than as a given?

I have divided the research into three parts. First, and most obvious, the bibliography will present citations on Milk as Labour and Commodity. Second, and inspired by the film, the bibliography will present citations on Milk, Embodiment and the Politics of Health. Last, and perhaps the one that has the potential of exploring the bigger questions, the bibliography presents Milk as Cultural Image and Narrative Device. I hope to open up conversation with these findings, and I hope it incentivises you to look into Milk throughout different systems of meaning. I hope that this can inspire or inform any projects, practices or research that can make use of this type of annotation. And last, I hope you forgive me for being so late with the post this time. The life of a graduate student that is also employed (win) does not allow for much personal exploration.

Milk as labour and Commodity

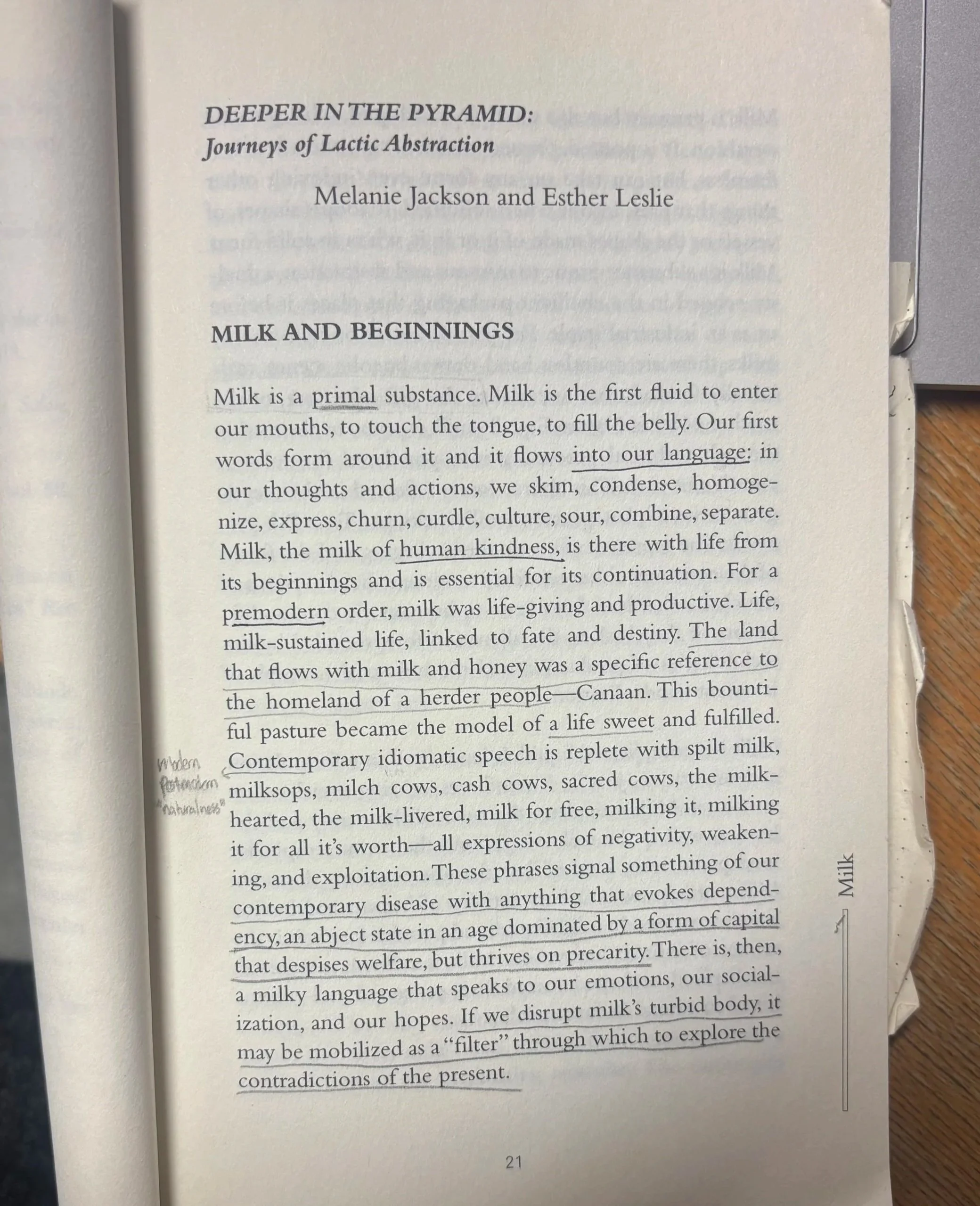

1.“Deeper in the Pyramid: Journeys of Lactic Abstraction” The Microbiopolitics of Milk. Sternberg Press, 2022.

This wonderful essay, written by Melanie Jackson and Esther Leslie, goes through the the journey of the ‘idea’ of Milk. The text starts out with establishing its value, its condition within our consciousness:

“Milk is a primal substance. Milk is the first fluid to enter our mouths, to touch our tongue, to fill the belly” (21)

From there it proceeds to trace milk’s transformations: from natural, biological beginnings to processed, commodified, technoscientific entities. It examines how milk takes shape in various forms (liquid, solid, powder, emulsion) and how its packaging, marketing, and materiality reflect industrial, cultural, and economic imperatives.

The essay situates milk in mythic terms (“the land that flows with milk and honey”) and links that to modern commodity networks and the abstract “grid” of milk production and packaging. It highlights the “milk grid” (for example, the network of dairies, tanks, distribution) and the geometric abstraction of milk containers (Tetra Pak’s pyramid shape) as symbolic of the technocratic reorganisation of milk.

“Milk flows across the political body, its stream an emblem of progress and the perfectibility of modern times. Situating milk as infinitely available, white, aseptic, and central to the adult Western diet was a quest of modernity. The mass industrialisation of milk indicates a mode of industrial metaphysics: an abstraction from its associations. with female human and nonhuman animal lactation and its transformation into a de-gendered industrial staple.”(25)

This passage articulates how milk functions as a modernist emblem of abundant progress, stripped of its embodied origins in female lactation and recast as an abstract, sanitised commodity central to Western nutritional ideology. It shows how industrialised milk becomes a de-gendered, de-specied material whose cultural power lies in its apparent neutrality and infinite availability.

2. The case of the 2008 Chinese milk scandal

The 2008 Chinese milk scandal constitutes one of the most devastating examples of milk’s transformation into a biopolitical commodity under late capitalist conditions. The incident centered on the discovery that milk and infant formula produced by several Chinese companies had been adulterated with melamine. Melamine is a chemical used in the manufacture of plastics and fertilizers. It contains nitrogen, and when added to milk, it inflates protein readings during standard nutritional tests. The adulteration was carried out to meet the protein standards required for commercial sale and to reduce production costs.

This contamination led to severe health consequences. Infants and young children who consumed the affected formula suffered from kidney stones and renal failure. Official reports confirmed that six children died from complications, and hundreds of thousands were hospitalized. The crisis brought to light the pressures faced by dairy farmers and producers within an expanding and competitive industry. It also exposed gaps in regulatory oversight and raised concerns about the integrity of supply chains and food testing procedures.

3. “Got Milk” campaign (1993-2014), Milk Processor Education Program (MilkPEP)

click on the images to see adds

While researching this bibliography, the most referenced and recognisable cultural presence of milk arose from these infamous ads. The “Got Milk?” campaign launched in 1993 for the California Milk Processor Board and were later licensed nationally by Milk Processor Education Program. It emerged at a moment when fluid milk consumption in the United States was stagnating, which prompted dairy interests to reposition milk, among being a wholesome nutrition, as a culturally potent, desirable product.

The “Got Milk?” campaign emerged at a moment when declining milk consumption prompted the dairy industry to rethink the substance’s cultural positioning. Through its ads, the campaign introduced scenarios in which a person’s routine was suddenly disrupted because milk was missing. The campaign introduced an aesthetic that foregrounded milk within familiar, domestic scenes, drawing on settings already central to most viewers’ experience of the substance. In these images, milk appeared alongside emotions such as reassurance or comfort, subtly framing it as part of daily rhythms and personal habits. This approach invited viewers to engage with milk through a language of feeling and routine rather than through attention to agricultural practices or industrial systems. By placing milk within these culturally resonant narratives, the ads contributed to a version of milk that operated more as a shared cultural symbol than a visible product of labour and supply chains.

The milk moustache became a key visual motif. Worn by athletes, celebrities, and even fictional characters, it marked the drink as part of a lifestyle with psychosocial and ‘health’ aspirations.

Milk, Embodiment and the Politics of Health

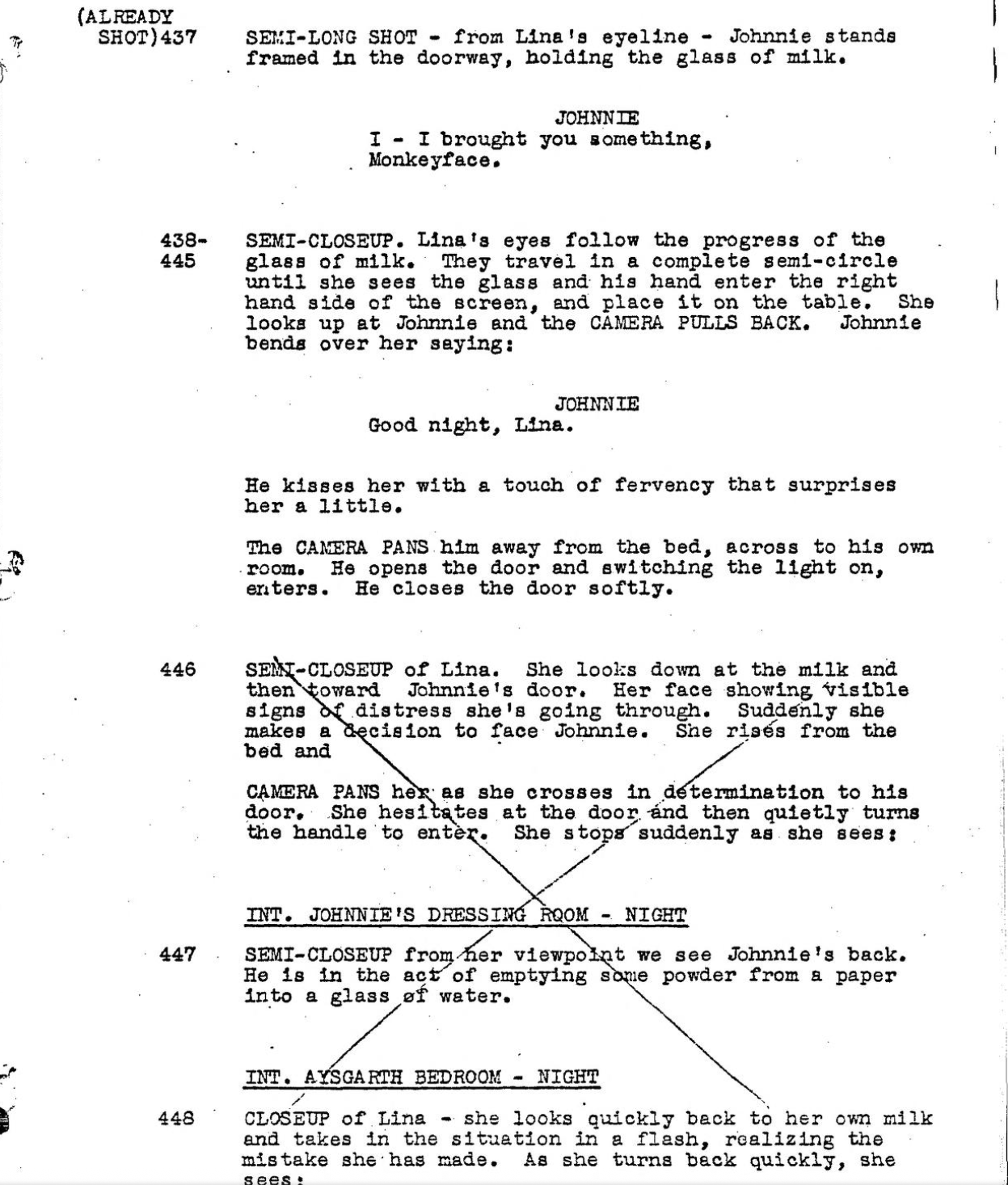

Suspicion (1941) screenplay, Samson Raphaelson, with contributions by Joan Harrison and Alma Reville

Suspicion (1941) began as a novel titled Before the Fact, a psychological thriller by Anthony Berkeley Cox (writing as Francis Iles). The film adaptation, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and written by Samson Raphaelson and Joan Harrison, follows the story of Lina, a sheltered heiress who marries a charismatic but financially reckless man, Johnny. As the narrative unfolds, Lina begins to suspect that Johnny is plotting to kill her, possibly for her inheritance.

In the screenplay, the glass of milk functions as a key symbolic object. Its most notable appearance occurs late in the story, when Johnny brings Lina a glass of milk as she lies in bed, visibly anxious and suspicious. The scene is meticulously constructed: the dialogue is sparse, the direction instructive, and the milk becomes a charged object. In the text, the glass is the focal point of both Lina’s fear and the audience’s uncertainty. The screenplay makes clear that Johnny’s act could be either one of care or something more sinister. Lina refuses to drink it, presenting a kind of rejection of the intimacy that milk represents.

2. “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States.” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 23, no. 1, 2008, pp. 15–47 by Heather Paxson

Heather Paxson’s article “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States” was published in Cultural Anthropology in 2008, a moment of heightened discussion around food politics and public health regulation. This period saw a growing interest in food safety, driven in part by industrial food scares and by the rise of the local food movement. Raw milk and raw-milk cheese became flashpoints within this discourse, framed by regulators as potentially hazardous, while many small producers and consumers saw them as symbols of authenticity and ecological care. Paxson situates her article within this tension, engaging questions that were pressing in anthropology at the time: how biological life becomes an object of governance and how cultural practices challenge or rework that governance. She writes, “dissent over how to live with microorganisms reflects disagreement about how humans ought to live with one another” (15), which foregrounds a key issue of the time: the relationship between scientific authority, embodied risk, and forms of everyday care. The article remains significant as an early and influential articulation of “microbiopolitics,” a concept that extends biopolitical theory to the level of microbial life, and current political discourse connecting the raw milk movement to conservative politics.

3. Convox Dialer Double Distance of a Shining Path (2011) by Anicka Yi

Anicka Yi, Convox Dialer Double Distance of a Shining Path, 2011, recalled powdered milk, abolished math, antidepressants, palm tree essence, shaved sea lice, ground Teva rubber dust, Korean thermal clay, steeped Swatch watch, aluminium pot, cell-phone signal jammer and electric burner, 58 x 38 x 38 cm. Courtesy: 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse

Anicka Yi’s Convox Dialer Double Distance of a Shining Path includes powdered milk that was recalled from circulation, placing it in a context where the ordinary function of milk (as nourishment) is no longer secure. Once recalled, the milk becomes a material associated with failure in systems that attempt to standardise quality and safety. Yi often works with smell as a primary sensory element. The presence of powdered milk, especially in a non-edible state, opens up questions about how biological materials shift from food to matter for aesthetic contemplation.

When milk becomes something to smell or observe, rather than drink, our consciousness is confronted by its altered state. Recalled milk suggests a breakdown in trust or reliability, and powdered milk emphasises the distance between the original substance and its processed version. In this installation, these qualities allow Yi to explore a relationship between the body and substances that are meant to sustain it. Instead of being absorbed, the milk is encountered as something mediated by systems of industrial production and regulation. The artwork encourages the reflection on the conditions under which nourishment, safety, and embodied experience become entangled with modern processes of refinement and control.

Milk as Cultural Image and Narrative Device

“The Sour Milk of Etymology”,Oxford University Press Blog, May 2022, Anatoly Liberman

“The Sour Milk of Etymology” examines the word “milk” as a linguistic artifact with ancient Indo-European Roots. I enjoyed this text, because it places its attention to milk as a symbolic entity embedded in language, carrying cultural associations that predate its commodification or medicalisation. The etymological method traces how milk accrues contradictory connotations throughout history, with its substance liked to purity, nurture and origin, yet it is also vulnerable to souring and spoilage. These dual semantic trajectories expose milk as a figure oscillating between sustenance and corruption.

Anatoly Liberman observes that “‘origin unknown’” best describes the English word milk, since “no one can say why milk is called milk.” He traces the material substance back to Indo-European roots where “the first contact of humans with milk must have been through breast-feeding,” long before cow milking became standard. Liberman points out how the word for milk in Slavic languages stems from terms meaning “puddle” or “liquid,” which points to how milk may once have been linguistically associated with fluidity rather than nourishment. These linguistic layers suggest how milk holds cultural significance shaped by the common ideas of origin and purity, while also reflecting processes of change and interpretation over time and throughout culture.

2. “Wine and Milk.” In Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers, 58–61. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972 by Roland Barthes

Roland Barthes’s essay “Wine and Milk,” published in Mythologies in 1957, investigates how everyday substances carry cultural meaning. In postwar France, Barthes observes that wine had become embedded in national identity, especially as a marker of vitality, conviviality, and even moral clarity.

“Wine is felt by the French nation to be a possession which is its very own, just like its three hundred and sixty types of cheese and its culture. It is a totem-drink.” (58)

He describes wine as a drink that circulates through all levels of society, one that appears natural in its ubiquity, but is in fact made meaningful through discourse and symbolism. It gives form to values associated with Frenchness: strength, pleasure, and productivity.

Barthes then turns to milk. Instead of presenting it as a counterpart to wine, he situates it in a separate cultural narrative. Milk appears in postwar France as a substance associated with restoration and care rather than celebration or sociality.

“Wine is mutilating, surgical, it transmutes and delivers; milk is cosmetic, it joins, covers, restores. Moreover, its purity, associated with the innocence of the child, is a token of strength, of a strength which is not revulsive, not congestive, but calm, white, lucid, the equal of reality.” (60)

Barthes points to its cultural associations with childhood and nourishment. In the postwar context, political figures like Pierre Mendès-France used milk in public settings as a statement of healthy, rational governance. Milk became a product tied to a different kind of national rhetoric, one that foregrounded health and stability.

3. Safe (1995) by Todd Haynes

And finally, the film that re-inspired this research. In Safe, director Todd Haynes situates the character of Carol White (played by Julianne Moore) within the polished trappings of affluent suburbia. Carol’s illness has no clear medical explanation, and the camera often lingers on the pristine spaces she inhabits, coded through pastel colours, wide frames and a pervading stillness.

Milk appears during scenes that show Carol at home. She drinks it during seemingly ordinary moments, such as at breakfast or after returning from errands. These scenes help place milk within her daily routine. Later in the film, a doctor tells Carol to stop consuming dairy products. This moment introduces a change in how milk functions within the story. Milk, usually presented as a regular part of her diet, becomes something that might be a threat to her health. It raises questions about how the body responds to commonly known nurturing substances and how medical advice can alter the idea of the liquid that gives life. Milk completely vanishes in the film as an object within the home, and its meaning changes once it is potentially linked to Carol’s illness.

I would love for anyone that has seen this to contact me so we can chat further about it. I am intrigued by the reference to “The Yellow Wallpaper” and female hysteria, and can see how these connect to common connections of purity and sanity to milk. Go to p.3 to contact me!